🌟 Paradise [2]: Abu Zayd's Verse on the Wine Heavenly; شراب بهشتی را بشناس

Such a Drink that would make All His Contentment 'Scanty', His Love Poetry 'Feeble'.

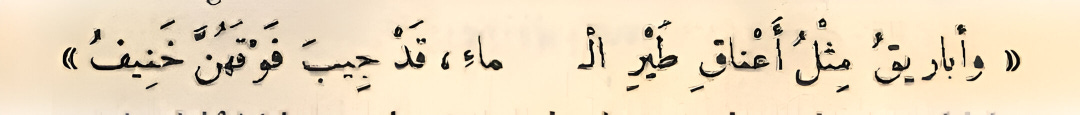

“ And Jugs with spouts like the necks of waterfowls

their Tops slit open by a hand of unerring purity ”

🔵 Understanding The Arabic Words In Context:

وأباريقُ — "And pitchers": This is the plural of ibriiq (إبريق), a vessel for pouring, especially water or wine. In Qurʾānic and classical usage, it often describes elegant jugs in paradise (Surah al-Insān, 76:15).

مثل أعناق طير الماء — "like the necks of water birds”. مثل means ‘like’.

أعناق is the plural of ʿunuq (neck), used for graceful forms.

طير الماء literally means "birds of water" — evoking not only form but also motion and purity.

قد جيب فوقهنّ حنيف — "Above them, a ḥanīf has cut [open the tops]":

قد جيب: "Has been slit" — j-y-b is the same root used for juyūb (neck openings of garments), here used figuratively for the opening or slitting of the pitcher top, like collars being tailored.

فوقهنّ: "above them" — likely referencing the mouths of the pitchers, spatially located atop the necks.

حنيف: Here interpreted as an agent noun, meaning a pure or upright one (from ḥ-n-f), possibly metaphorical: the capping or fashioning of the pitchers was done by someone spiritually upright, pure, or of heavenly status.

=> Read The arabic Verse Now; “وأباريقُ مثلُ أعناقِ طيرِ الماءِ، قد جيبَ فوقهنّ حنيفُ”

🟢 Intricacies of the Verse:

This verse consists of 2 hemistichs (شطران), following a structured classical poetic format.

[ Recite the verse slowly to yourself. The following would feel much more clearer :D ]

=> The verse opens with a conjunction (wa) for continuation. The verse employs the following poetical devices.

Tashbīh (simile):

"أباريقٌ مثلُ أعناقِ طير" of the necks of birds compared to the slender necks of pitchers.

Majāz Mursal: Use of “جيـبَ” — literally "to slit/cut open at the collar" — applied metaphorically to openings of the pitchers (their tops).

Personification: The pitchers are "capped" as though clothed, almost feminized through “فوقهنّ”.

Wordplay on ḥanīf, lending both a meaning of “pure/true” and possibly alluding to early Islamic monotheism if interpreted in broader metaphorical context.

=> The rhyme letter (ḥarf al-rawī) is fāʾ (ف). In Arabic, Verses were often remembered by heart and referred to the letter with which the verse ended (e.g Taiaat & Lamiaat). This letter would be the equivalent of the Persian/Urdu Radif. In this verse, the letter is fāʾ (ف).

The qāf, ḥāʾ, and nūn used throughout the couplet provide internal music and breath-like flow. Hanīf1 (خَنيفُ) ends the bayt, with an echoed ū and f sound, a hard and clear closure.

“أباريق” is a classical word with Qura’nic echoes (cf. Surah Al-Insān), It has a very interesting use here with a sort of a paradisiacal connotation.

🔵 Analyzing The Verse:

There's a layered symbolism to be explored here.

The jug necks compared with bird necks depict here qualities like grace, slenderness, delicacy. "حنيف": Can mean that the fashioning was done by someone upright or pure (perhaps an angelic being), or that the vessel itself embodies purity (untouched, for the pure). جِيبَ: Verb used for slitting collars of garments in classical Arabic — transferred to pottery, showing the anthropomorphism of vessels. There's also a Quranic echo: in Surah Al-Insān (76:15-16), similar descriptions of pitchers in paradise are given using the same word “أباريق”.

🔘 Root Analysis and Their Classical Usages:

🟡 Identifying the Meter (البحر الشعري):

First hemistich (ṣadr):

The verse is written in Bahr - At Tawil; the syllables of which can be mapped on and checked as here.

وَأَبَارِيْقُ مِثْلُ أَعْنَاقِ طَيْرِ الْمَاءِ

⏑ – – ⏑ – – ⏑ – ⏑ – – ⏑ –

mapped onto;

فَعُولُنْ مَفَاعِيلُنْ فَعُولُنْ مَفَاعِلُنْ

Breakdown:

وَأَبَا → ⏑ – – → فَعُو

رِيْقُ مِثْلُ → ⏑ – – → لُنْ مَفَا

أَعْنَا → ⏑ – – → عِيلُنْ فَعُو

قِ طَيْرِ → ⏑ – ⏑ → لُنْ مَفَا

الْمَاءِ → – – → عِلُنْ

قَدْ جِيبَ فَوْقَهُنَّ حَنِيفُ

Scansion:

⏑ – – ⏑ – – ⏑ – ⏑ – –

Mapped onto;

فَعُولُنْ مَفَاعِيلُنْ فَعُولُنْ

Breakdown:

قَدْ جِي → ⏑ – – → فَعُو

بَ فَوْ → ⏑ – – → لُنْ مَفَا

قَهُنَّ → ⏑ – – → عِيلُنْ فَعُو

حَنِيفُ → ⏑ – – → لُنْ

“

The root ح-ن-ف fundamentally means 'to incline away from one path toward another.' This inclination is what defines the ḥanīf - not necessarily purity, but devotion through conscious turning.

In religious contexts, this inclination is toward monotheism, away from falsehood. But in poetry, particularly when wine is involved, ḥanīf can represent someone who has secluded themselves from worldly concerns for the sake of a singular devotion.

So when we read 'قد جيب فوقهنّ حنيف,' we're seeing these vessels opened by someone who has devoted themselves exclusively to this task - whether a heavenly being preparing paradise's vessels or an earthly wine server who has forsaken all else for this pleasure.

The Quranic echoes of 'أباريق' in surah Insan, support this dual reading, allowing the verse to operate simultaneously in paradisiacal and worldly realms. The interpretation of ḥanīf merely as 'pure' misses this rich duality that the poet likely intended.

”

A succint addition by one of our reader expands on the commentary on the word حنيف; which I’ve added here.

While the provided interpretation of حنيف as 'pure or upright one' captures one dimension of the term, it misses crucial semantic layers that enrich our understanding of this verse.

The root ح-ن-ف fundamentally means 'to incline away from one path toward another.' This inclination is what defines the ḥanīf - not necessarily purity, but devotion through conscious turning.

In religious contexts, this inclination is toward monotheism, away from falsehood. But in poetry, particularly when wine is involved, ḥanīf can represent someone who has secluded themselves from worldly concerns for the sake of a singular devotion.

So when we read 'قد جيب فوقهنّ حنيف,' we're seeing these vessels opened by someone who has devoted themselves exclusively to this task - whether a heavenly being preparing paradise's vessels or an earthly wine server who has forsaken all else for this pleasure.

The Quranic echoes of 'أباريق' in surah Insan, support this dual reading, allowing the verse to operate simultaneously in paradisiacal and worldly realms. The interpretation of ḥanīf merely as 'pure' misses this rich duality that the poet likely intended.