🌟 Frivolities & Anxieties of the Illusory World: Conversing with Adi Ibn Zaid At-Tamimi in Heaven [2]

Obfuscations, Ruminations, Meanderings, all Unimportant in Heaven!

✨ The Story Continues:

Ibn Qarih fulfills his wish getting to hear the famous qasida in ‘ص’ by Adiyy Ibn Zayd al Ibadi himself. He then goes on to Glorify God, and thanking the great poet.

Ibn Qarih says, “Well done, by God, well done!1 were you stagnant water you would never turn stale or stink!”

“Well, I came to you for I was anxious” said Ibn Qarih. “About a verse of yours… which Sibawayh2 went on to quote as lingustic evidence on a point of grammar3” (reciting the following verse to the poet!)

ʾarwāḥun muwaddaʿun ʾam bukūru || ʾanta, fa-unẓur li-ʾayyi ḥālin taṣīru

A parting at dusk, or a farewell at dawn?

You there! Reflect what fate will yours become

This was the afterlife, and upon hearing this couplet and what Ibn Qarih had said Adiyy replied “Please, Spare me all that nonsense! Actually, I was a great hunter in the Perishable World!”.

“Speak, would you like us to mount two horses of Paradise and to drive them toward herds of wild cows, strings of ostriches, flocks of gazelles, and droves of onagers? For hunting is a pleasure for which I have always enjoyed.”. Adi presents this wish of his to Ibn Qarih and the story continues…

[Lets understand this classical verse further & learn Arabic using this couplet!]

🟢 Understanding The Arabic Words in Context of The Verse:

Couplet 1:

أَرَواحٌ مُوَدَّعٌ أَمْ بُكُورُ

أنت، فانظر لأيِّ حالٍ تَصِيرُ

💎 Meanings:

أَرَواحٌ —> Departure (at forenoon); from ر-و-ح, often refers to departing in early part of the day (possibly late morning).

مُوَدَّعٌ —> One who is bid farewell; passive participle from و-د-ع, “to bid farewell.”

أَمْ —> Or?; interrogative disjunction used in comparative or speculative contexts.

بُكُورُ —> Early departure (at dawn); noun from ب-ك-ر, indicating movement in the early morning.

أنتَ —> You (masculine singular); subject pronoun.

فَانْظُرْ —> Then look!; imperative of ن-ظ-ر, “to see, consider.”

لِأَيِّ —> To what / for what kind of; interrogative + genitive construct.

حالٍ —> State / condition / fate; feminine noun, here indefinite and general.

تَصِيرُ —> You shall become / turn into; verb from ص-ي-ر, meaning “to become.”

🔵 Intricacies of the Verse:

The first line of the verse uses parallel nouns (arāḥun / bukūru) set up as a question: “Is this a departure in the late morning, or an early one?”. Bukurun Suggests youth, fresh starts, hope, ambition, or the first steps in a journey, perhaps even referring to naive optimism. (which I have with this stack :D). Arawahun, on the other hand suggests weariness, regret, closure, retrospective wisdom, end of life, or even death, perhaps a metaphor for life ending suddenly or slowly.

Second line shifts to a direct address: a rhetorical pivot into self-exhortation that: You! look to what fate you turn into.

The ambiguity between dawn and dusk is one creating tension amplifying a sense of imminence: “Whenever it is, the end is coming—so reflect!” By not anchoring the time, it creates a subtle existential uncertainty, a device similar to Qur’anic warnings: “So when the trumpet is blown…” indicating the time to not be the point but our readiness for the the ‘good night’.

Even grammatically, the structure of this couplet reflects the ambiguity and urgency of the situation. Sībawayh analyzed the first hemistich as lacking a main verb, which adds to the feeling of a hanging question, like the silence before a judgment.

The poem poses life as a journey toward death, uncertain in timing. Will your departure be gentle (arāḥun) or sudden (bukūru)? Either way, you’ll have to face what you'll become… This turns and beckons to be a veiled reminder of the Day of Reckoning: that man must reflect upon his spiritual end-state before it’s too late. Psychologically speaking, there is a reflections of what could be accounted as existential dread; the movement of time, the coming of change, and our deciding of how we will be shaped by it.

🔘 Roots of words and Their Classical Usages:

🌟 Forthcoming:

Adi, instead of caring about lexical complexities and trivialities of poetry, instead presents his wish to go out and ride with Ibn Qarih.

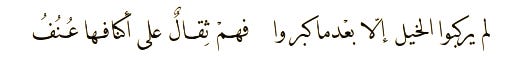

Ibn Qarih responds sharply, a dialogue which we will follow in the next post alongside the following verse which is part of our protagonists’ response.

Footnotes:

Performative Poetry:

Poetry, specifically in the Medieval Arab, context was performative. Praise was given to a poet on how well he could recite his poetry and how clean their verses sounded. This later on came to be the Ijaaz of the Holy Quran. This is why Ibn Qarih praises the way he does here, which may come across odd to an unfamiliar audience.

Sībawayh (c. 760–796 CE), a Persian by origin, is considered the father of Arabic grammar. Despite never being a native Arabic speaker, his magnum opus, Al-Kitāb ("The Book"), became the foundational text of Arabic grammar and linguistics. Written with rigorous logic and deep observation, it systematically codified the rules of classical Arabic at a time when the language was evolving rapidly. Interestingly, Sībawayh never visited the Arabian Peninsula—his understanding came entirely through scholarly transmission and sharp intellect.

The way modern Arabian Dictionaries and Philology work is; Classical Pre-Islamic & Quranic Arabic (600 CE) is weighed as standard gold Arabic. We traceback the words we speak and the language we use to that Arabic. Hence the reference to Sibawayh, an Early Islamic grammarian. Early grammarians treated poetry as linguistic precedent. We speak of relationship between language and meaning today but here we find, intentionality in meaning was already being debated centuries ago!

In his Kitāb, Sībawayh cites this couplet to defend a grammatical anomaly:

“The word أنتَ at the start of the second line appears disjointed. Sībawayh argues it's actually the subject of an implied verb, to mean perhaps ‘do you wonder?’ or ‘are you aware?’ — and the following فانظر makes it explicit.”

This implies a syntactic ellipsis (ḥadhf).

This matches what Ibn Qarih tells Adi in the original Arabic, ““Sībawayh claims that ‘you’ could be taken as a nominative, on account of an implied verb, which is explained by the following word, ‘see!’ But I think this explanation is far-fetched and not, I think, what you intended.”