An Ode Recited in The Lovely Gathering [3]: The Heavenly Banquet Continues

A Misattributed Poem to The Genius of Dhubyan is recited

✨ The Story Continues:

“Who are these celestial personages?” to only be answered by “The ones whose immediate presence you so desired!” To which Ibn Qarih and his party only Praised God.

Ibn Qarih says “O Reciters! (referring to the new party that had dropped in consisting of Abū ʿAmr al-Māzinī7, Abū ʿAmr al-Shaybānī8, Abū ʿUbaydah9, ʿAbd al-Malik10), The Qasida of An-Nabigha rhyming in ‘d’, but before reciting it tell me…,

"Do you recite its verses in second person or in the first person singular? ‘when you (or I) look,’ ‘when you (or I) touch,’ ‘when you (or I) stab,’ and ‘when you (or I) withdraw:’"

“As second person singular,” The reciters answered.

Ibn Qarih continues, “Here is our master poet, Abū Umāmah, The Nabigha of Dhubiyan, and he said, he prefers the verses to be recited in first person singular. He informs me that all of his verses were written in direct speech put into the mouth of al-Nuʿmān.”

Upon this, the transmitters then recite this Ayah of the Holy Quran. (An-Naml: 33)1

وَٱلْأَمْرُ إِلَيْكِ فَٱنظُرِى مَاذَا تَأْمُرِينَ

The matter rests with you, so consider what you will command.

When they had accepted the Authority of the An-Nabigha, Ibn Qarih then felt no further discussion necessary, and asked the transmitters to recite to him these following verses

Alimmā ‘alā al-maṭmūrah al-muta’abbadah Aqāmat bihā fī al-marba‘ al-mutajarradah

A stop by the concealed, everlasting dwelling,

Where she once resided in the bare, open pasture.

Muḍammaḫatan bi-l-miski makḫḍūbatun al-shawā

Bi-durrin wa yāqūtin lahā mutaqalladah

Perfumed with musk, her limbs stained (with dye),

Adorned with necklaces of pearls and rubies.

Ka’anna thanāyāhā wa mā dhuqtu ṭa‘mahā Majājatu naḥlin fī kumaytin mubarradah

Her teeth, though never kissed, I liken still

To honey pure in cooled crimson wine.

Li-yaqrar bihā al-Nu‘mān ‘aynan fa-innahā Lahū ni‘matun fī kulli yawmin mujaddadah

May al-Nu‘mān’s eyes find rest in gazing upon her,

For she is a blessing to him, renewed each day.

“How Strange! I dont ever recall ever dabbling in such a style…2 ”, says the Nabigha of Dhubyan

“Amazing! Who is it then who has knowingly attributed these verses to you?”

“It was not attributed to me deliberately”, says An-Nabigha, “but perhaps by mistake and pure misconception. Perhaps the verses were by Thalaba Ibn Sa’ad.”

Then the other al-Nābighah, of the tribe of Jaʿdah, joins in and says, “Once, in the days before the coming of Islam, a young man accompanied me; we were going to al-Ḥīrah. He recited this very poem to me as his own composition.”

He told me that he belonged to the tribe of Thaʿlabah ibn ʿUkābah. But when he arrived to the royal court, King al-Nuʿmān was ill and Tha’labah was not granted access to him.”

“In all probability that is what happened.” Al-Nābighah al-Dhubyānī remarked on this.

[Lets understand this classical verse further & learn Arabic using this couplet!]

🟢 Understanding The Arabic Words in Context of The Verse:

Couplet 1:

ألِمّا عَلَى الْمَطَمُورَةِ المُتَأَبَّدَةْ

أَقامَتْ بِهَا في الْمَرْبَعِ الْمُتَجَرَّدَهْ

💎 Meanings:

ألِمّا: “Stop by!” — an imperative of affectionate visitation.

المطمورة: From طمر — something buried or hidden; here, a metaphorical image of an abandoned or secluded campsite.

المتأبّدة: From أبد — “deserted forever” or "wilderness-haunted" — a place where no man treads; wild, isolated.

;

أقامت بها: “She settled in it” — refers to a beloved or maiden.

المربَع: The spring pasture — a poetic topos for beauty and romance.

المتجرّدة: From تجرّد — “laid bare,” “isolated,” or “unadorned,” implying either nudity, emotional rawness, or physical solitude.

Couplet 2:

مُضَمَّخَةً بِالْمِسْكِ مَخْضُوبَةٌ الشَّوَى

بِدُرٍّ وَياقُوتٍ لها مُتَقَلَّدَهْ

💎 Meanings:

مضمّخة بالمسك: “Smeared with musk” — evoking sensual allure.

مخضوبة الشوى: Her limbs (shiwā) are dyed — typically with henna; a sign of beauty and sensual readiness.

;

بدُرّ وياقوت: With pearls and rubies — vivid metaphor for jewelry, but possibly a stand-in for teeth and lips.

متقلّدة: Hung around her — necklace, ornaments, or even metaphorically “adorned with beauty.”

Couplet 3:

كَأَنَّ ثَناياها وَما ذُقتُ طَعْمَها

مَّجاجةُ نَحلٍ في كُمَيْتٍ مُبَرَّدَهْ

💎 Meanings:

ثناياها: Her teeth — white, shining, upper teeth; typical image of poetic beauty.

ذُقت طَعمها: “Though I have not tasted her” indicating restraint, unfulfilled longing.

;

مجاجة نحل: The extracted essence of honey — honey spit; luscious and pure.

كميت مبرّدة: “Chilled dark wine” — kumeit is reddish-brown wine. Together, a sensual simile of taste and luxury.

Couplet 4:

لِيَقْرَرْ بها النعمانْ عَيْنًا فَأِنَّهَا

لَهُ نِعْمَةٌ في كُلِّ يَوْمٍ مُجَدَّدَهْ

💎 Meanings:

ليقَرّ بها: “Let al-Nuʿmān’s eye find peace in her” — a poetic blessing or wish.

نُعمان: The Lakhmid king al-Nuʿmān ibn al-Mundhir, known for his patronage.

عينًا: Eye — synecdoche for contentment and vision.

;

نعمة: Blessing, delight.

مُجدّدة: Renewed — eternal, recurring joy, highlighting paradise-like continuity.

🔵 Intricacies of the Verse:

These verses portray the archetype of the idealized beloved, grounded in the lush lexicon of pre-Islamic poetic motifs: musk-drenched skin, henna-stained limbs, isolated campsites that echo love’s memory, and the longing tempered with the poet’s tasteful restraint.

Beneath the couplets also lies the subtle tension: this woman lives in a past that is at once vividly present and yet buried, a ghost in a sacred spring meadow. The deserted wishfulness is not just physical; it's symbolic of buried passions, exiled joy, or memory entombed in longing.

Her sensory beauty (musk, henna, jewels) is enhanced by the tactile image of majājah nahl (the essence of honey) in kumayt mubaradah (the brown-reddish wine, coupling of taste and fragrance, suggesting an intoxication deeper than mere physicality.

The final verse shifts toward the king al-Nuʿmān, The patron of this beauty and its spiritual beneficiary. the poet wishes his (The Kings) eyes to find continual delight in her. This could be interpreted as a gesture of poetic gifting.

Al-Maʿarrī reflects on the tradition of Arabic language, and makes the point to bring forth the original poet in Risalat Al Ghufran, and have him explain how this verse can not be his at all. This shows the expertise Ma’ari had in Arabic linguistics and tradition.

He attributes it a misconception in attribution (from Thalaba to al-Nābighah) but also how beauty, longing, and poeticism can still be enjoyed and delighted in whilst in Paradise, when apparently the verses may in fact be merely carnal and hollow.

🔘 Roots of words and Their Classical Usages:

🌟 Forthcoming:

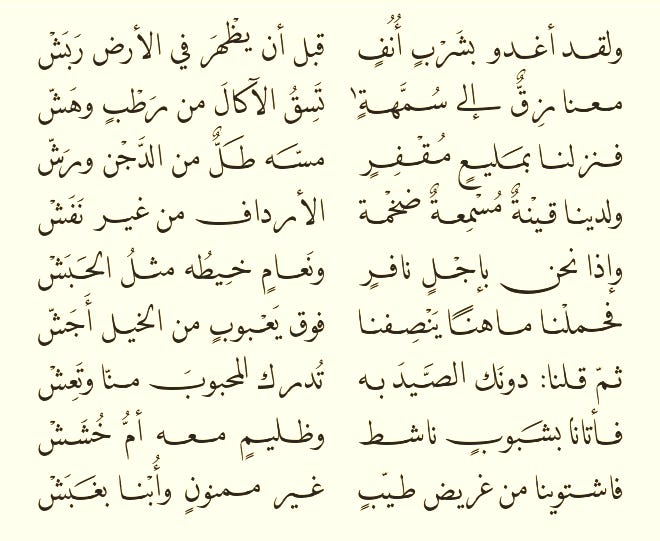

A misattribution? but then Nabigha of Ja’adi’s verses are recited by the reciters. Which also turns out to be a special case. We will look at this verse in our next post.

⭐ Footnotes:

Where counsellors of Queen Sheba address her. A similitude in speech to the talk of Paradise as indicated by Al-Ma’ari. For ofcourse, is not the Quran the highest standard of speech?

The verses in question reflect a stylized, highly ornate form of Arabic poetry marked by tashṭīr (splitting the verse into short, rhythmically balanced segments), internal rhyme, and dramatic pausing, diverging sharply from the unified, flowing rhythm of traditional qasīda. Essentially the mold of qasida is not conformed to in such poetry.

For example, in the opening line'; "أَلِمّا عَلَى الْمَطَمُورَةِ المُتَأَبَّدَةْ / أَقَامَتْ بِهَا في الْمَرْبَعِ الْمُتَجَرَّدَهْ" the hemistichs each end in a feminine rhyme (-ah sound), and the syntax invites a pause at both mid-line and line-end, breaking the classical expectation of reciting the full bayt as one continuous breath.

Similarly, the line "مُضَمَّخَةً بِالْمِسْكِ مَخْضُوْبَةٌ الشَّوَى / بِدُرٍّ وَيَاقُوتٍ لَهَا مُتَقَلَّدَهْ" includes an internal conceptual and rhythmic pause at "مَخْضُوْبَةٌ الشَّوَى", forming a near-enjambment (to flow or not to flow).

This heavy use of internal cadence and rhetorical embellishment, alongside lush sensory imagery (e.g., musk, jewels, honey), aligns the piece more with later Abbasid badīʿ poetry and even maqāmah-style sajʿ than with the austere eloquence of early desert verse.

When An-Nābigha al-Dhubyānī, hears these lines and says, "ما أذكر أني قلت شيئًا من هذا النمط" ("I don’t recall ever composing in this manner"), he is rejecting not the content, but the style. A florid, over-decorated, rhythmically fragmented mode alien to his own classical tradition, which favored longer metrical lines, clear imagery, and dignified, continuous rhythm.