🌟 The Legendary Qasida in 'ص'. Ibn Qarih's Instant Request to Adi Ibn Zaid upon their Meeting.

Fulfilling the wish of our favorite poets reciting us their works themselves.

✨ The Story Continues:

Ibn Qarih finished the conversation with ‘Abid ibn Al Abras by asking him, “Have you any knowledge of Adi Ibn Zayd al Ibadi?”. ‘Abid then pointed to Adi’s house, for which then, our protagonist departed.

Upon Meeting Adi1, Ibn Qarih asks him on how he managed to cross the الصراط (The Path) for He was reputed to have died a Christian.

“Indeed, I was Christian!” replied Adi, “And anyone who was a follower of Prophets before Muhammad ﷺ was sent, shall suffer no harm; and only retribution came to those who worshipped Idols.”

Ibn Qarih then requested in heaven, finally in front the Poet he had long adored in the Transient World to recite the following famous Qasida of his, rhyming in ‘ص’ (S’ad).

Abligh khalīli ʿAbda Hindin falā || zulta qarīban min sawādi al-khuṣūṣ

Convey to my comrade, ʿAbd of Hind

May you ever dwell near the heart of the Khuṣuṣ,

Muwāzī al-fawrati aw dūnahā || ghayra baʿīdin min ghumayri al-luṣūṣ

Where danger surges (Al Fawrah) or just on its side,

Not distant from land of Ghumayr Al Luṣuṣ

Tujnā laka al-kam'atu rabʿiyyatan || bil-khabbi tandā fī uṣūli al-qaṣīṣ

The fruits be yours, spring-borne, sweet and succulent,

Unearthed discreetly from where the soft grasses lie (Qaṣiṣ).

Taqniṣuka al-khaylu wa taṣṭādaka al- || -ṭayru wa lā tunkaʿ lihawā al-qanīṣ

Where horses hunt for you, the falcons pursue in flight

And you never flinching from distractions in your game.

Taʾkulu mā shiʾta wa taʿtallu-hā || ḥamrāʾa malḥuṣṣun ka-lawni al-fuṣūṣ

feasting on all that you desire, and drink,

Wine from Al-Huss, sleek, red colored like gemstones

Ghuyyibta ʿannī ʿAbdu fī sāʿati al- || -sharri wa junnibta awāna al-ʿawīṣ

You were not near me, ʿAbd, when evil fell

You were spared the hour I knew too well.

Lā tansayanna dhikrī ʿalā ladhdhati al- || -kaʾsi wa ṭawfin bil-khudhūfi al-naḥūṣ

Forget not my memory, in the pleasure of the cup

Nor when drawing lots with your unlucky stones.

Innaka dhū ʿahdin wa dhū maṣdaqin || mukhālifan hadya al-kadhūbi al-lamūṣ

You are a man whose word holds tight,

Refused to be cunning, to be led by lies.

Yā ʿAbdu hal tadhkurunī sāʿatan || fī mawkibin aw rāʾidan lil-qanīṣ

O ʿAbd, do you still recall the hour

When we rode in procession, scouting our hunt?

Yawman maʿa al-rakbi idhā awfaḍū || narfaʿu fīhim min najāʾi al-qalūṣ

That day, when the riders surged in a line

And we loosed the swiftest camel to shine?

Qad yudriku al-mubṭiʾu min ḥaẓẓihi || wa al-khayru qad yasbiqu jahda al-ḥarīṣ

Indeed! sometimes the slow reaches his fate

And indeed the good outpaces the too eager too keen.

Falā yazal ṣadruka fī raybatan || yadhkuru minnī talafī aw khulūṣ

May doubt not haunt your chest with fear

Of my demise or of my escape, unclear.

Yā nafsu abqī wa-ttaqī shatma dhī al- || aʿrāḍi inna al-ḥilma mā in yanūṣ

O soul, endure and guard against the slander

For one who possesses honor, surely doesn’t waver

Yā layta shiʿrī wana dhū ʿajjatin || matā arā sharban ḥawālī aṣīṣ

O If only I knew amidst my state of restless turmoil,

When again shall I find drinks surrounding me from earthen pots (Asiṣ)

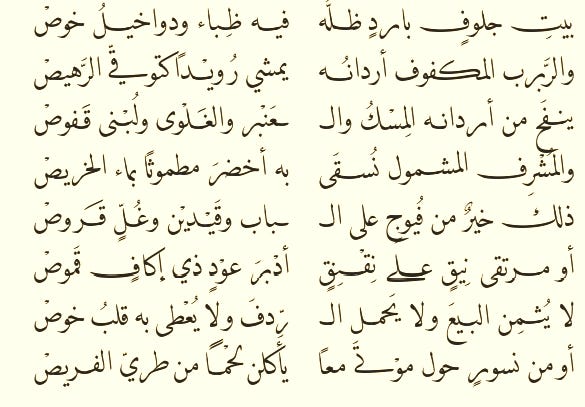

Bayti jalūfin bāridin ẓilluhu || fīhi ẓibāʾun wa-dawākhīlu khuṣṣ

In some wide hut, with its shade soft and wide,

With gazelle-like charms, and teeming fronds inside.

Wa al-rabrabu al-makfūfu ar-dānuhu || yamshī ruwaydan ka-tawaqqā al-rahīṣ

And a princely she-camel, swathed at the sides,

Moving slow, like a youth in elegant strides. (Rahiṣ)

Yanfahu min ardhānihi al-misku wa- || al-ʿanbaru wa al-ghalwā wa lubnā qafūṣ

From her flanks fragrance of musk and amber divine,

Glowing with ghalwa and lubnā; sweet scents confined.

Wa al-mushrifu al-mashmūlu nusqā || bihi akhḍara maṭmūthan bimāʾi al-kharīṣ

And Upon that upland, swept with cooling breeze,

We drink lush green water pressed in dates with ease. (Khariṣ)

Dhālika khayrun min fuyūjin ʿalā al- || -bābi wa qaydayni wa ghullin qarūṣ

Far better that than crowds at some harsh gate,

With shackled wrists and chains that chafe with weight.

Aw murtaqā nīqin ʿalā niqniqin || adbari ʿūdin dhī ikāfin qamūṣ

Or climbing hills on a balking beast,

Old, ill-saddled, its value decreased

Lā yuthminu al-bayʿa wa lā yaḥmilu al- || ridfa wa lā yuʿṭā bihi qalbu khuṣṣ

It brings no price, nor bears a guest,

Not worth a twig or a palm-leaf pressed.

Aw min nusūrin ḥawla mawtā maʿan || yaʾkulna laḥman min ṭarīyi al-farīṣ

Or like the vultures circling corpses bare,

Tearing soft flesh in the open air.

“SubhanAllah. Well done, By God… SubhanAllah, Well done…” Said Ibn Qarih.

“Were you stagnant water, you would never turn stale or stink!” as he basked in joy with the poetry he heard from the Abu Sawada Adi Ibn Zayd Al Tamimi, author of this Qasida himself.

[Lets understand this classical verse further & learn Arabic using this couplet!]

🔴 Introduction To The Qasida:

The qasīda in ‘ṣ’ is a rich elegy of friendship, regret, political exile, and philosophical musing on fate, liberty, and honor. Delivered originally as a letter-poem to a companion named ʿAbd, the piece begins in pastoral tones, invoking lush imagery of the wild;

particularly mushrooms picked in spring, birds and horses capturing prey, only to spiral gradually into more complex reflections on betrayal, nostalgia, and spiritual alienation. Beneath the seemingly bucolic veneer resides profound alienation of a court poet unjustly imprisoned or marginalized, crafting coded indictments against tyranny and disloyalty.

The Qasida overgoes alot of themes. & I loved unpacking every bit of i. The longing for lost companionship, the fickleness of fortune, and the symbolism of captivity. Be it iron fetters or the constraints of false societyemerge repeatedly, the images juxtapose purity of nature’s creatures with the tribal codes of honor. Linguistically, we find in the the poem a blend of pre-Islamic lexical richness with courtly sophistication, marked by rare compounds, visual verbs, and textured metonyms. (I had a long hard time finding many of the roots and confirming them in the lughah I use).

The rhythm of this poem is a bit heavy with the rhyme being ‘ص’. The very movement of the verses mirrors a transition from physical displacement to existential exile. It is that Adi was Arab nobility and formed what was a part of the Sassanian Bureaucracy. The themes contained therein are all so that only someone of ʿAdī's cultural straddling could produce.

🟢 Understanding The Qasida in Context of The Verses:

Couplet 1: أبلِغ خليلي عبدَ هِندٍ فلا

زُلْتَ قريباً من سَواد الخصُوص

أبلِغ Root: بَلَغَ — “To reach / convey.”,

خليل: Close friend, confidant (y - suffix)

عبدَ:ʿAbd: Servant/slave; here a proper name, short for ʿAbd Hind

هِندٍ: Proper name — a female name often found in pre-Islamic contexts

فلا زلتَ 2: “May you not cease...”,

زِلتَ: From زَالَ ; “To cease to be”; here used idiomatically: “May you remain…”

قريباً: Near, close

من: From

سواد: Lit. "blackness" in classical Arabic: used metaphorically for the settled area of land, cultivated terrain, or dense populated region

الخصوص: Al-Khuṣūṣ; possibly a specific locality of Arabia.

Zuhayr opens the Qasida with an urgent call to convey a message. He invokes ʿAbd Hind, likely a friend-figure, and blesses him with a rhetorical supplication: “May you remain ever close to the swād of al-Khuṣūṣ.” The word sawād3 implies not only geographical proximity but proximity to civilization, intimacy, and safety.

Couplet 2: مُوازي الفُورة أو دونها

غيرَ بعيدٍ من غُمير اللُّصوص

مُوازي : Root: وزى (و ز ي) “To be parallel to” Muwāzī: one who is level with, adjacent to الفُورة: Root: فَوَرَ — “to boil, to surge” Fawrah: metaphor for intensity, turbulence, agitation. Likely refers to a location near hot springs or terrain that “boils” with danger/activity

أو دونها: Or Beneath, below, not quite reaching

غير بعيدٍ: Not far

من: From

غُمير: Rare word. Root: غ م ر Ghumayr: diminutive form of ghamar, referring to a small hidden hollow, possibly with ambush connotation

اللُّصوص: Thieves, robbers, possibly from لصّ — to steal, sneak.

[غُمير اللُّصوص4 is likely to refer to a place in Arabia as well]

The second verse immediately introduces the counterpoint: an edge of chaos. Whether near the fawrah (a bubbling, potentially dangerous place) or even just short of it, the tone hints at precarity. He is near Ghumayr al-Luṣūṣ — a dark ravine where thieves might lie in wait literally, or a spot in Arabia. Reference is to the thin line between safety and peril, between civilized nearness and the lurking unknown. This could be a metaphor for being emotionally “close to ruin,” or teetering near the edge of one’s own destruction. (A theme which will play on as the Qasida develops)

Couplet 3: تُجْنَى لك الكمْأة رَبعيّة

بالخَبِّ تنْدَى في أصُول القَصيص

تُجْنَى From ج ن ي — To gather, harvest; Passive verb: “is gathered for you”.

لك: For you.

الكمْأة: Truffle; a prized underground fungus; classical delicacy, especially in winter/springtime. In pre-Islamic culture, considered a gift from the desert.

رَبْعِيّة: From رَبِيع; springtime, Here: "of the spring season" — lush, fresh, soft.

بالخَبّ: To gather stealthily / dig softly / forage with tact, Could also refer to secret uncovering of the truffle, "With stealth" or "through subtle extraction".

تَندَى: Root ن د و — To be moistened, dewed, softened. “Becomes moist”; truffle softens or glistens with moisture.

في أصول: In the roots, foundations

قَصِيص: A kind of grass or shrub — low-lying desert flora. The truffle grows beneath it

This verse paints a lush sensual landscape: truffles in springtime, moist and hidden beneath desert grasses — delicacies extracted through quiet and careful digging. This evokes not just natural abundance but also intimate, rare delights revealed to the one who knows where and how to look. Truffles also have a significance in Islam.5 The mood being tactile and earthy. This will pivot instantly in the next verse

Couplet 4: تَقْنِصك الخيلُ وتصطادك ال

طّيرُ ولا تُنْكَع لهْوَ القنيصْ

تَقْنِصُك: From ق ن ص — To hunt. 2nd person object: “You are hunted” (lit. “The horses hunt you”)

الخيل: Horses, likely those of hunters

وتصطادك: From ص ط د — To catch, to hunt (with traps or birds) "And you are caught" (by birds)

الطير: Birds — trained falcons or hawks, used in Arab hunting

ولا تُنكَعْ: To flinch, pull back, be stopped from, Tunkāʿ here: “You are not deterred”6

لهوَ Play, pastime, amusement

قنيص: Hunting game / the act of hunting; So: “You are not held back from the joy of the hunt”.

We have the introduction of pivot; with use of the 2nd person reference direct to hunting. Desert is known to be symbolic for hidden treasure, it is also symbolic for danger: & the joys of hunt called to

Couplet 5: تأكل ما شئتَ وتعتلُّها

حمراءَ مِلحُصّ كلوْن الفُصوصْ

تأكل ما شئتَ: You eat whatever you wish. Full freedom in luxury; an image of unrestrained provision

وتعتلّها; From ع ل ل — multiple possible shades: to return repeatedly to drink/feed, or to affect (esp. a mount or a camel) Here: likely to ride her repeatedly, as in “you mount her and go”.

حمراءَ: Red-colored; adjective describing a she-camel or horse

ملْحُص: From ل ح ص, smooth-skinned, sleek, often refers to a well-bred racing camel or horse, esp. one slick in movement or coat

كلون الفصوص Like the color of pearls/jewels فَصّ (plural: فصوص) = a gem or stone set in a ring, Together: "reddish and slick, like polished jewels"

The first line is luxuriant: the addressee (likely ʿAbd) eats his fill, rides a sleek red steed. here, power and freedom combined with grace and style. The simile “like the color of jewels” is particularly arresting as it evokes preciousness and rarity.

Couplet 6: غُيّبتَ عنيّ عبدُ في ساعة الـ

شَّرّ وجُنِّبتَ أوانَ العويصْ

غُيِّبْتَ عنِّي:You were removed from me, you were absent

عَبْدُ: Address to ʿAbd (ibn Hind); familiar tone, possibly affectionate or lamenting

في ساعة الشر: In the hour of evil / misfortune. A moment of calamity could be war, betrayal, hardship

وَجُنِّبْتَ From ج ن ب — you were spared / kept away. Passive: you were made to avoid / to be kept out of

أوان العويص- : time, moment (أوان) + عويص: hardship, complexity, turmoil. Lit. “The time of entanglement”; a moment when things are dire, tangled, hard to navigate

Then comes the iltifaat:7 this figure of ease and elegance was absent at the speaker’s moment of deepest need. There's deep emotion embedded here: betrayal, perhaps, or simply the ache of misfortune unfolding without one’s companion nearby.

Couplet 7: لا تنسَيَنْ ذِكْري على لذّة الـ

كأس وطوْفٍ بالخَذوف النَّحوصْ

لا تنسَيَنْ: Do not forget! (Emphatic command, second person)

ذِكْري: My memory, mention of me

على لذّة الكأس:In the pleasure of the cup. Refers to drinking, particularly wine — a common image of forgetfulness and indulgence

وطَوْفٍ بالخَذوف النحوص: Wandering, roaming (طوف); especially for pleasure, خذوف: From خ ذ ف, pebbles used in divination, or reference to fortune-telling games, نحوص: Plural of نحصْ; ominous, unlucky

→ Taken together: “your roaming games with ominous stones” = superstitious or playful diversions under unlucky omens.

On to the theme of longing and loyalty now. moments of pleasure; wine, games, perhaps friends, to which Adi pleads, “Do not forget me then.” A poignant anxiety is found here. Will Abd’ Hind remember his loyal friend, not in hardship, but in joy?

Couplet 8: إنّك ذو عهدٍ وذو مَــصْــدَقٍ

مُخالفًا هَدْيَ الكَذوب اللَّموصْ

إنك ذو عهدٍ: Truly, you are a man of loyalty (covenant)

وذو مصدقٍ: And a man of truth / truthfulness

مخالفًا هدي الكذوب اللموص: Against (مخالفًا), هدي: way, manner, الكذوب: habitual liar: اللموص: a rarely used epithet8; connotation of someone low, sneaky, nosy, or prone to shameful slander.

—> Taken together; “Opposed to the path of the liar.”

This verse reaffirms ʿAbd’s character; the speaker still holds faith in his virtue.

It’s a moral anchor: You are not like those who forget. You’re better than that. This pair frames a sort of noble expectation: akin to:

In your bliss, don’t erase me.

For I believe you still walk the path of the loyal.

Couplet 9: يا عبدُ هل تذكُرني ساعةً

في موْكبٍ أو رائدًا للقنيصْ

يا عبدُ: O ʿAbd! (direct address to his friend)

هل تذكرني ساعةً: Do you remember me for a moment...: “Hour” here is metaphorical — a brief moment, an instance

في موكبٍ أو رائدًا للقنيصْ : a caravan, a procession (موكب)

رائدًا: a scout, someone sent ahead to find pasture or game

القنيص: game/hunting; here likely refers to a hunting expedition

→ Taken together; Whether in the caravan or as one sent ahead for the hunt.

The mood here is both nostalgic and noble, pulling ʿAbd back to a time of shared movement, where their paths were united and defined by forward thrust.

Couplet 10: يومًا مع الرّكب إذا أو فضوا

نرفع فيهمْ من نَجـاء القَـلـوصْ

الركب: the mounted group / travel company

أوفضوا: moved quickly, hastened

—> together; “One day, when the caravan pressed forward swiftly”

نرفع فيهم من نجاء القلوص

نرفع: literally “we lifted,” here connoting “we urged forward,” or “brought forth”

نجاء: swift (from نجو: to escape or be saved), so “fast” or “fleet”

القلوص: a young she-camel — known for speed and endurance9

—> together; “We raised up from among them the swiftest of camels”

The focus returns on the remembrance of passed days i.e a shared experience of hardship and nobility. Recall to frequent hunting trips perhaps the poet had with his friend.

Couplet 11: قد يُدرك المبطئُ من حظّه

والخيرُ قد يسبِق جهْدَ الحريصْ

قد: indeed / possibly

يُدركُ: he attains / he reaches (from أدرك)

المُبطئُ: the one who is slow / the delayed one

من: from / of

حظّهِ: his fortune / his luck

و: and

الخيرُ: the good / benefit / well-being

يسبق: precedes / outpaces

جهدَ: effort / toil

الحرِيصْ: the eager one / the one who is greedy or overly keen

Probably the most visibly profound couplet of the Qasida. Sort of an aphorism even. Invoking ideas such as qadar and tawakkul, he contrasts the slow (mubti) with the overly eager (harees)10. The verb pairing yudrik vs yasbiq also creates a beautiful inner symmetry11: one ‘reaches’, the other is ‘outpaced’. The whole idea here being that negation of the notion that success is only a product of effort. It gestures toward divine decree, chance, or hidden blessing (barakah) all the whilst noting that on account of envy and arrogance: the slow & hesitant, though less equipped, may receive what the zealous miss entirely.

Couplet 12: فلا يزلْ صدرُك في ريْبةٍ

يذْكر مني تَلَفي أو خُلوص

فلا: then do not / so never

يَزَلْ: cease / stop (a jussive verb here with negation — classical idiom)12

صدرُكَ: your chest / bosom / heart (metonymy for emotional state)

في: in

ريبةٍ: doubt / suspicion / misgiving

يَذكُرُ: he remembers / mentions

مني: from me / about me

تلفي: my perishing / my loss

أو: or

خلوص: my salvation / escape / purification

The existential theme continues. فلا يزل صدرك في ريبة" is idiomatic. “may your heart never remain in doubt”; as a sort of tanbeeh. The alternation between talaf (destruction, death, loss) and khuluṣ (purity, salvation, or even vindication) indicates the uncertainty here. Perhaps Is he dead? Did he survive? Did he reach freedom?

Couplet 13: يا نفسِ أبقي واتَّقي شتْمَ ذي ال ـ

أعراض إنّ الحِلمِ ما إن يَنوصْ

يا نفسِ: O my soul

أبقي: remain / endure / persist (imperative)

واتقي: and guard against / fear / beware (imperative)

شتم: abuse / insult / verbal slander

ذي الأعراضِ: one who possesses honor / the honorable person

إن: indeed / surely

الحِلمَ: forbearance / patience / composed dignity

ما: not

إن ينوص: does not shake / waver / bend

The focus goes on the poet Zuhayr with the admonition now being reflective. He asks for him"الحِلم" (ḥilm) which is actually more than patience stands for moral excellence13; . Our poet asserts that this quality is unshakable, not even by the gravest insult. The structure ما إن 14ينوص uses both negation + emphasis, reinforcing: It is not at all the way of ḥilm to sway in face of insult; meaning, true dignity stands still.

Couplet 14: يا ليت شِعري وانَ ذو عَجّةٍ

متى أرى شَرباً حَوالي أصيصْ

يا ليت: Oh would that / if only

شعري: I knew / my knowing

وأنا: while I am / and I am

ذو: possessor of / in a state of

عجّةٍ: a state of turmoil / confusion / commotion (can imply mental noise or worldly burden)

متى: when

أرى: shall I see

شربًا: drinking / drinkers

حوالي: around me / surrounding me

أصيص: earthen pot (used for wine or plants)

The verse starts out with a sigh here. This verse expresses a state of wishful longing, weariness and an extremely evocative image for which he dreams.

Couplet 15: بيتِ جلوفٍ باردٍ ظلُّه

فيه ظِباء ودواخيلُ خوصْ

بيتِ: a house / dwelling

جلوفٍ: large, spacious, or gaping (sometimes means rudely wide; here likely descriptive of a rustic hut)

باردٍ: cool

ظلّه: its shade

فيه: in it

ظباءٌ: gazelles / antelopes (graceful female figures metaphorically)

ودواخيلُ: inner areas / inner chambers / enclosures

خوص: palm fronds (or woven palm-leaf mats)

The scene shifts from the poet himself to a house now; as the landscape of the qasida broadens. The effeminate themes join in as part of the poets longing.15

Couplet 16: والرَّبرب المكفوف أردانُه

يمشي رُويدًا كتوقى الرَّهيصْ

و: and

الرَّبربُ: a large, strong she-camel (robust female camel)

المكفوفُ: with sides covered / draped (possibly by baggage or cloth)

أردانُهُ: its flanks / sides

يمشي: it walks

رُويدًا: slowly / gently / at ease

كتوقى: like one cautious / wary / careful

الرَّهِيصْ: a young man with delicate or graceful steps; or a light-footed mount (implies elegance)

The imagination continues. In the form of a sensory crescendo now. Slow movement, draped elegance. The verse showcases the affection the Arabs had with the camel and the extent to which they had the ability to tell allegories through it. “Rab-rab” (الرَّبرب) is A rare, majestic term evoking noble camel femininity; perhaps symbolic here too for grace or a personified ideal woman.

Couplet 17: ينفَح من أردانه المِسكُ والـ

عَنْبر والغَلْوى ولُبْنى قَفُوصْ

ينفَحُ: exhales / emits a fragrance

من: from

أردانهِ: its flanks / sides

المسكُ: musk

والعنبرُ: and ambergris

والغلوى: (possibly) a fragrant plant resin / aromatic oil (obscure, likely local perfume)

ولُبنى: and lubnā (a resinous tree with sweet scent)

قفوص: bound-up / enclosed / secured (possibly meaning carried in packages or tied as perfume sachets)

The scene continues, the gracefulness of the camel is described with a strong focus on the aroma, the smell and the scene. scent satchels tied to the camel’s saddle; a detail of aristocratic leisure travel. Ornamentations & Drapings, all paint a very strong scene.

Couplet 18: والمُشرِف المشمول نُسقَى

به أخضرَ مطموثًا بماء الخريصْ

و : and

المُشرِفُ : the elevated land / upland plain

المشمولُ : wind-swept / breezy

نُسقَى : we are given to drink / we drink

به : from it

أخضرَ : green (metaphorically fresh or lush, often for wine or juice)

مطموثًا : strained / filtered / pressed (from طمث meaning to purify, clarify)

بماءِ : with water of

الخَريصْ : khariṣ: fresh dates (or date wine / juice of ripe dates)

Strong imagery again in the form of upland windswept place (al-mushrif al-mashmūl) elevation may be taken as spiritual here too. Whe one finds drinks a greenish liquid, likely a euphemism for date wine, perhaps non-fermented or gently fermented, described with a sensual vocabulary: filtered, lush, mixed with the essence of ripened fruit.

This here is described as the peak/in-extremis of life’s joys which marks as the point of inflection the Qasida.

Couplet 19: ذلك خيرٌ من فُيوجِ على الـ

باب وقَيْديْن وغُلٍّ قَروصْ

ذلك : that

خيرٌ : is better

من : than

فُيوجٍ : crowds / herds / throngs

على البابِ : at the door

وقيدينِ : and two chains (suggesting bound wrists or ankles)

وغُلٍّ : and a shackle (around the neck)

قَروصْ : tight / biting / chafing

We’re now in the themes of what may be for the Arab mind, the worst of life. The first is a captured man in a crowd. With restrained shackles on him.

Couplet 20: أو مرتقى نِيقٍ على نِقْنِقٍ

أدبرَ عودٍ ذي إكافٍ قموصْ

أو : or

مرتقى : a climb / an ascent

نيقٍ : of a she-camel (esp. tall, good for riding)

على : on

نِقْنِقٍ : a stony, rough, or steep mountain path

أدبرَ : old, worn out / turned away

عودٍ ": beast of burden / mount

ذي : possessing

إكافٍ : a padded saddle

قموص : skittish, uncooperative, hard to ride

Second is having a worn-out beast struggling up a steep mountain, its saddle slipping, its temperament unpredictable, its worthless burden unwanted.

Couplet 21: لا يُثمِن البيعَ ولا يَحمل الـ

رِّدفَ ولا يُعْطى به قلبُ خوصْ

لا : not

يُثمِن : yields a price / valued in sale

البيعَ : the sale

يَحمل : bears / carries

الرِّدفَ : the one riding behind (rear rider)

ولا : nor

يُعْطى : is given / offered

به : for it (i.e., the camel)

قلبُ : the heart

خوص : of palm fiber (i.e., even something as trivial as palm fiber is not given in exchange)

The presented image of utter uselessness continues. You have a burden that you can’t even sell. “قلبُ خوص” (a heart of palm-fiber) is a deliberate insult; here that nobody would even trade the camel for such a worthless item. This is like saying: not worth a torn shoelace.

Couplet 22: أو من نسورٍ حول موْتَى معًا

يأكلن لحمًا من طريّ الفريصْ

أو : or

من : from / of

نسورٍ : vultures / eagles (but more accurately vultures in this context)

حول : around / circling

موتى : dead ones / corpses

معًا : together / all at once

يأكلن : they devour / eat

لحمًا : flesh16

من : of

طريّ : tender / fresh

الفريصْ : the trembling flesh (often refers to the quivering part near the chest or shoulder, e.g. heart meat)

A conclusion with an image most striking. Life and then an image of a dishonorable death. Vultures circling and devouring tender flesh ; with no one left to bury you either. For the nomad Arab, perhaps this speaks of the ultimate humiliation: when one’s body, once proud, becomes meat for beasts. the classical motif of the failed warrior or forsaken man, dying alone, without companions, without rites, left for birds

🔘 Roots of words and Their Classical Usages:

🌟 Forthcoming:

After delighting in this Qasida, Ibn Qarih puts forward his wish to ask Adi about a couplet of his used as an authority in Grammar.

We will understand the following couplet, and go ahead with the story in upcoming posts.

Footnotes:

ʿAdī ibn Zayd (d. ~600 CE):

A Christian Arab poet from al-Ḥīrah in Iraq. Often seen as a representative of pre-Islamic Nabataean influence in Arabic poetry. He worked closely with the Lakhmid court and was famed for his elegant, concise, and oft-veiled advice or critique couched in beautiful verse. He is the same as the one featured in “Adî ibn Zayd and the Princess Hind”, from the tale found in the Arabian Nights.

See more: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adi_ibn_Zayd

Balāgha (Rhetoric) in “fa-lā zilta”:

This structure is a duʿāʾ (supplication), using negation to affirm — "May you never cease being..." ; a classical idiomatic Arabic blessing. This can also be found alot in Saj’ verses

Swād (السواد):

Technically means "blackness," but in early Arabic, it refers metaphorically to settled lands, cultivated villages, or populated territory. Hence the phrase: sawād al-ʿIrāq (the fertile Mesopotamian belt). So “sawād al-Khuṣūṣ” might not be a place-name but a poetic metonym for comfort, roots, security.

Ghumayr al-Luṣūṣ:

An unusual construction. “Ghumayr” is a rare form — diminutive of “ghamr,” which is used in: وغمرهم النهر : “The river overwhelmed them.” But also linked to ambush: a hidden hollow where luṣūṣ (robbers) might hide. Hence this may, beyond perhaps an actual geographical place be a brilliant metaphorical flourish implying lurking danger even in seeming stillness.

Truffles in Pre-Islamic Culture: Known as kamʾa, they were highly prized. Prophet Muhammad ﷺ even said: "The truffle is from manna and its liquid is healing for the eye." (Ṣaḥīḥ Muslim 2049). In pre-Islamic poetry, they are symbols of desert luxury, and being offered them is a gesture of favor or closeness.

https://sunnah.com/muslim:2049f

Tunkāʿ (تُنكَع) is a rare but potent word. From the root نكع which carries senses of cowardice, backpedaling, or being stunned. Its usage suggests steadfastness in thrill, the joy not reduced by threat.

A common ancient poetic pattern: A scene of wealth or pleasure, followed by Sudden twist into emotional or existential rupture.

اللموص: Sibawayh (and later grammarians) discussed its root; possibly from ل م ص (to whisper/slander/suck), it has negative connotations of shamefulness, often used in satire.

القلوص: A poetic favorite — the she-camel in her prime. Light, swift, often described with elegance. Poets like Imruʾ al-Qays or Labīd use her as a symbol of vitality, beauty, and motion.

Harīṣ (حريص) is one of those powerful Arabic words that blend eagerness, greed, and obsessive concern — used even in the Qur'an to describe the Prophet’s deep concern for his people: حريص عليكم (eager for your wellbeing), Hence making the line not just about material striving; but also a philosophical critique of over-attachment.

The symmetric structure mimics that of many later Arabic proverbs. You’ll see its echo in sayings like:"ما كلُّ ما يتمنَّى المرءُ يُدركُهُ" And even in Qur’anic ideas such as: وَمَا تَشَاؤُونَ إِلَّا أَن يَشَاءَ اللَّهُ (You do not will unless Allah wills)

"فلا يزل": A common idiom in classical Arabic that survives into modern usage. Despite being literally “may it not cease,” it functionally means: may it never occur. Similar to English idioms like “God forbid” or “let it never happen.”

The Prophet ﷺ was called al-ḥalīm, and the Qur’an uses ḥalīm as one of Allah’s Names.

ينوص (from ناص) is extremely rare in modern Arabic. It originally referred to a camel lowering its neck when burdened — metaphorically: to sag under pressure. Here, it’s used to mean: ḥilm never bends, never sags under insult.

“ʿṢīṣ” (أصيص): Literally an earthenware jar, often used for wine or plants. Its presence in a poetry setting implies a relaxed gathering or private rustic feast. It carries pre-Islamic connotations of pleasure and escapism.

“Ṭarī” (طريّ): Used in the Qurʾān as well (“لحمًا طريًّا”) to describe the fresh meat of the sea, here being inverted: fresh human flesh being consumed. A powerful semantic reversal.